For the first time in Canadian history, a court has clarified the meaning of the phrase “place of origin” as referenced in section 12(1)(b) of the Trademarks Act (the “Act”).

Under this section, a trademark that clearly describes (or deceptively misdescribes) the “place of origin” of goods or services is generally unregistrable. The scope of the term “place of origin” has never been crystal clear. There are some obvious examples such as the names of cities, towns, roads, provinces, regions, and countries.

But what about other less obvious designations?

Could the term possibly include lines of latitude and longitude?

Well, based on a very recent decision of the Federal Court, the answer is YES.

In Nia Wine Group Co. Ltd. vs North 42 Degrees Estate Winery Inc., 2022 FC 241, The Canadian Federal Court ruled that “place of origin” should be broadly interpreted to refer to any geographical designation, even coordinates on a map or lines of latitude and longitude.

North 42 Degrees Estate Winery Inc (“North 42”) sought to register the trademark NORTH 42 DEGREES in association with the goods “wines” and the services “operation of a winery”. For context, North and 42 degrees are specific directional and numerical designations for a particular geographical location. In effect, North 42 Degrees (as read together) designates a specific line (space) that runs on the earth’s surface. North 42 operates its winery from a location that runs along the North 42 degrees line of latitude.

Nia Wine Group Co., Ltd. (“Nia Wine Group”) operates a winery in the Ontario Niagara region and sells wines throughout Canada under various brand names, including NORTH 43. It opposed North 42’s application to register NORTH 42 DEGREES as a trademark, on grounds, inter alia, that the mark is clearly descriptive of the place of origin of the goods and services (wines). In response, North 42 contended that NORTH 42 DEGREES was not a place of origin since it is not the actual name of a place or geographical location.

Section 12(1)(b) of the Trademarks Act reads as follows:

“Subject to subsection (2), a trademark is registrable if it is not:

whether depicted, written or sounded, either clearly descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive in the English or French language of the character or quality of the goods or services in association with which it is used or proposed to be used or of the conditions of or the persons employed in their production or of their place of origin;”

The Federal Court determined, from the standpoint of ordinary purposive interpretation, that the term “place of origin” is broad and should not be restricted to exclude terms that are not explicitly geographic names. Further, the court considered that the ordinary meaning of the word “place” (as per the Canadian Oxford Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary) was broad to include references to “a particular portion of space” or “a particular part or region of space” or “a spot, location and also a region or part of the earth’s surface.”

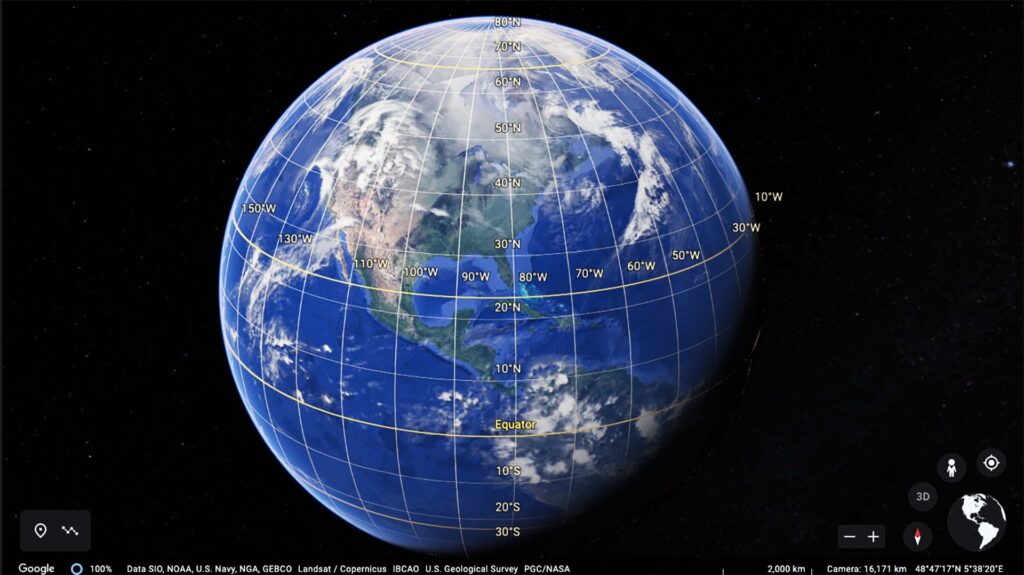

In that the word “place” includes specific references to spots on the earth’s surface, then lines of latitude and meridians of longitude would be considered as places, and, by extension, could be “places of origin” under section 12(1)(b) of the Act.

To elucidate further, the court offered the example of the Equator (zero degrees latitude), a well-known line of latitude to many. Imagine a scenario where an entity seeks to register “EQUATOR” as a trademark, for use in association with coffee, made from beans grown in the tropical climate of the Equator. The court opined that such an endeavour would likely flout the purpose of section 12(1)(b) of the Act since it would permit a monopoly over the use of the word “Equator”, thereby depriving potential coffee competitors of the opportunity to so describe their own coffee.

In the end, the court ruled that NORTH 42 DEGREES, being the name of a line of latitude, was, in fact, a place, and was not registrable under section 12(1)(b) since it clearly described the place of origin of North 42’s goods and services.

This case should certainly raise a red flag to brand owners looking to trademark the name of a geographical place or designation. One would be well advised to consult with a trademark lawyer before venturing along this path.

Notwithstanding the above, all hope is not lost. Depending on the circumstances, one could possibly navigate a route towards registering a name that may have some geographic significance. For example, if a proposed mark has several meanings, there may be room to argue that it is not clearly geographic. Another possible avenue to consider would be where the geographical name is not associated with the trademark applicant’s own business location and is not generally associated with the types of goods or services claimed. Also, if the brand is well-known and established, there may be room to argue that it has acquired distinctiveness as a trademark.

All in all, brand owners should exercise caution in adopting geographical names or designations as trademarks. If lines of latitude and longitude (such as the Equator and North 42 Degrees) are considered to be places, then the space to claim geographic references as trademarks has gotten very slim.